CIA Director John Brennan, who over a decade ago personally informed Jeffrey Sterling the agency was firing him, just released the results of a study on how the CIA should become more diverse.

CIA Director John Brennan, who over a decade ago personally informed Jeffrey Sterling the agency was firing him, just released the results of a study on how the CIA should become more diverse.

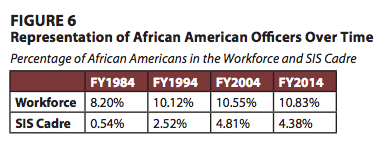

The recommendations — for example, that CIA should more aggressively mentor and promote its minority officers — and warnings — that the numbers of some minorities in top positions have actually been falling during a period of emphasis on diversity — read like object lessons one might take from Sterling’s own career. Sterling, after all, was denied key assignments because CIA managers thought he was “too big and too black” to plausibly adopt a particular cover.

In 2000, Sterling submitted an EEO complaint (see page 13 and following), alleging years during which he was not provided the same opportunity for success as white officers. He then sued (see page 17 and following), which led to his termination. The CIA got the lawsuit dismissed by invoking state secrets over the facts regarding Sterling’s employment. That background, DOJ claimed during Sterling’s trial, led Sterling to retaliate against the CIA by leaking details about the plan to deal blueprints to Iran.

Sterling’s troubles in New York happened just as he started to move into more senior positions.

The survey conducted as part of the study shows that many current CIA officers experience what Sterling did 15 years ago: a perceived lack of support from superiors.

Thus far, the study reads like many a corporatist effort to address diversity, with predictable buzzwords and recommendations. And for better or worse, Brennan’s recently announced agency reorganization aims to integrate some of the recommendations of the study, especially providing more career advancement for all officers.

But there is one recommendation that gets to the core of the problem, as evidenced by Sterling’s and other officers’ difficulties with CIA personnel management, but also for CIA’s efforts to meet a mission critical commitment to more innovative personnel overall: transparency.

The CIA study recommended the agency be more transparent about promotions and Equal Employment Opportunity complaints (with the implication that such transparency will instill trust among minority officers).

Transparency in the Agency’s promotions, assignments, awards, and other career management processes will allow Agency officers to (a) better understand their career development and (b) more effectively compete for promotions and assignments. The Agency should more widely publicize the results of career advancement of individual officers (e.g., promotions, selection for key training or educational assignments, etc.) as well as personnel actions (e.g., EEO complaints, grievances, “performance improvement plans,” etc.) to enhance the trust of the workforce in the system and improve accountability.

The evidence suggests, of course, that such transparency might actually confirm the fears of minority officers: there have been a number of lawsuits credibly alleging retaliation for EEO complaints in recent years: from women, people of color, and disabled officers. So there is no reason to believe that more transparency will foster trust, even if the notoriously secretive agency could manage such transparency.

Even more, the lawsuits alleging retaliation and the example of Sterling, who was targeted as a leaker in the wake of his EEO complaints, say something more about CIA’s inability to embrace transparency. On top of a secretive agency’s normal inability to share data about the career successes of its covert employees, the CIA also operates with an omertà like approach to protecting the agency. And when an officer makes a stink — including regarding diversity concerns — that is regarded as a threat to the agency.

As Sterling related in an ExposeFacts documentary released in May, when Brennan personally came down to tell Sterling he was fired, a colleague explained, “Well, you pulled on Superman’s cape.”

It’s not just that Sterling complained about his treatment. Throughout his trial, he was portrayed as a villain, in part, because, in complaining (and in purportedly exposing the CIA’s dodgy operations), he embarrassed the agency. That was a key part of the narrative DOJ used to convict Sterling.

And yet, this very same CIA believes it can adopt adequate transparency to hire and retain a more diverse workforce.